Short Summary

How to Take Smart Notes is a book on note-taking for students, academics, non-fiction writers, or anyone who wants to improve their thinking.

The key to good and efficient writing lies in the intelligent organization of ideas and notes. Instead of wasting your time searching for notes, quotes, or references, the Smart Notes method lets you focus on what counts: thinking, understanding, and developing new ideas.

Favorite Quote

"If you want to learn something for the long run, you have to write it down, If you want to really understand something, you have to translate it into your own words."

―Sonke Ahrens

Book Notes

How to Take Smart Notes explains the Zettelkasten (German for “slip-box”) note-taking methodology created by the German sociologist, Niklas Luhmann. The book covers how Luhmann organized his note-taking in a scalable way that allowed him to reach an unprecedented level of productivity with 58 books and 400+ articles being published by the end of his 30-year career.

After spending years commenting in the margins of text and collecting notes by topic, Luhmann realized his system wasn’t leading anywhere. While these techniques are better than not taking notes at all, he realized they all have one fundamental flaw: once written down, ideas stay passive; they do not mingle with each other. The sum of all notes does not amount to something greater.

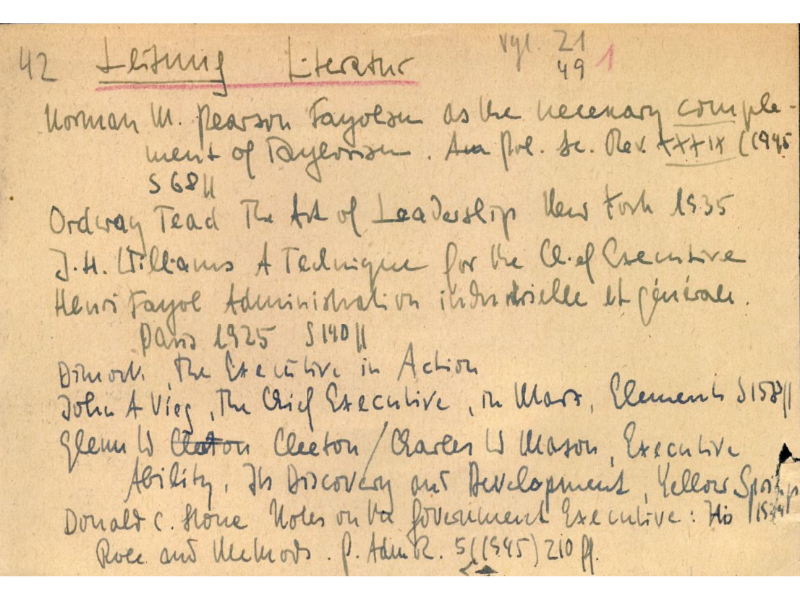

So Luhmann decided to turn note-taking on its head. Instead of adding notes to existing categories or their respective texts, he kept all of his notes in one place (the slip-box) by writing each note on an index card, giving it a distinct number, and connecting it to related notes.

Over the years, his slip box became a research database made up of thousands of index cards. But his slip-box was much more than just a collection of notes. It became an ever-growing external memory for developing thoughts, keeping biases in check, streamlining the writing process, and for sparking new ideas.

Here is how he used his system:

- Any idea he found interesting or useful is jotted down on an index card.

- Only one idea per card so that they could be individually referenced.

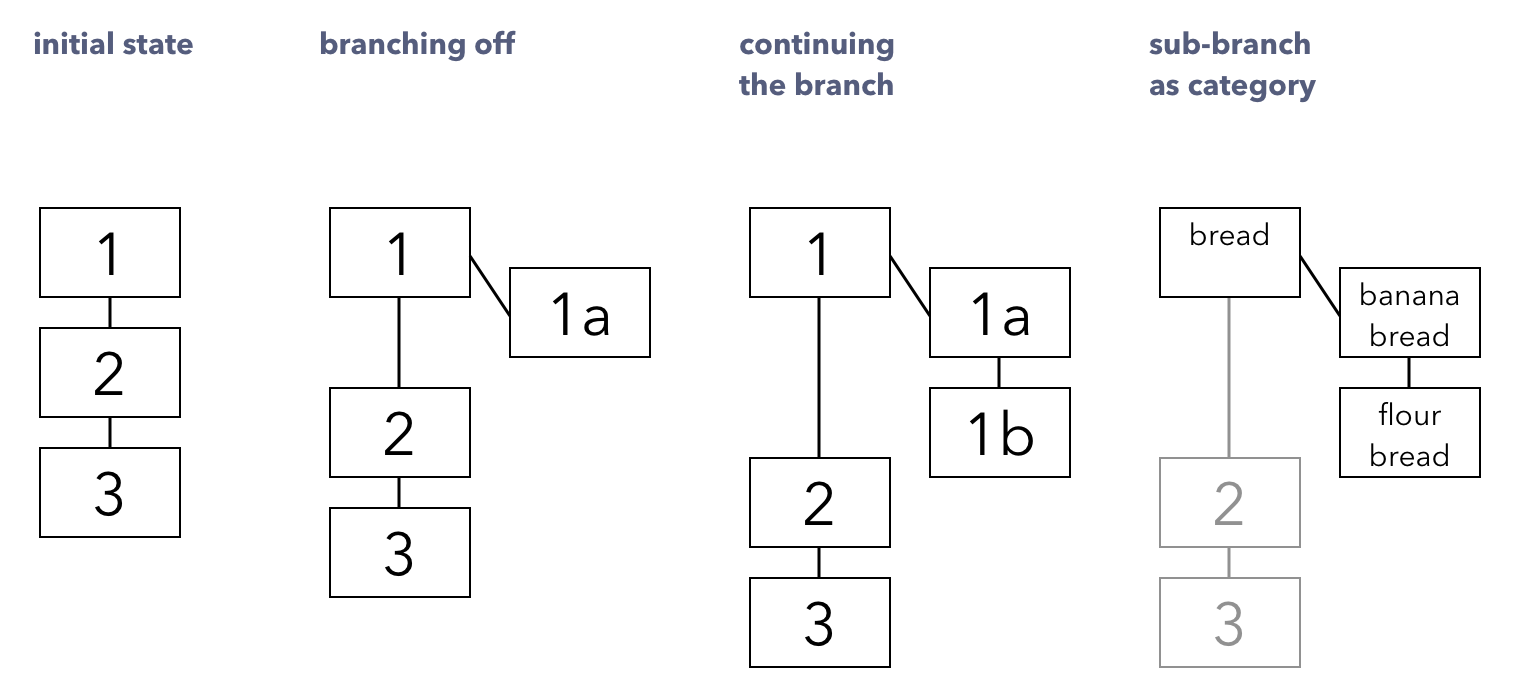

- Each card is numbered in the top-left corner. When a new card is added to an existing topic, use letters as suffixes (1a, 1b, 1c, etc.) and file it behind the most related existing note.

- As he consumed more information, he would create new cards, update or add comments to existing ones, and create links between existing cards.

- Build up note sequences around areas of interests. These sequences can later be used to write articles or books.

What differentiates the Smart Notes method from other note-taking methods is it recognizes that a note is only as useful as the context it is embedded in – its network of associations, relationships, and connections to other ideas. How you connect an idea is as important as the idea itself. Therefore a note then should be relevant to whatever is important to you, not just related to whatever you’re reading.

“Without understanding information within its context, it is also impossible to go beyond it, to reframe it and to think about what it could mean for another question.”

Instead of just highlighting or underlining passages, you want to manually create notes of the ideas you discover while you read. When you highlight or underline the text, you lose the context from which it was found. The highlight may seem important when you took it, but when viewed on its own, its importance or relevance may become lost.

You also don’t want to start with preconceived categories for filing your notes. Instead, let order emerge bottom-up by making connections between your notes and observe the differences between them. Creating a note should be decided by whether or not it adds value to your network by connecting to existing ideas or having the potential to connect to future ones.

“In the old system, the question is: Under which topic do I store this note? In the new system, the question is: In which context will I want to stumble upon it again?”

By focusing on what interests you, your intellectual development, topics, questions, and arguments will naturally emerge from within your slip-box. Deciding what you should write about will come automatically since you’re already working on existing interests and doing what is necessary to be informed.

The Eight Steps for Taking Smart Notes

When reading a book, you always want to have something to write with to capture every idea that pops into your mind. I prefer having a pen and Moleskine notebook next to me when I read but you can use whatever is convenient for writing down ideas wherever you go.

But whatever you choose, you want to write your notes down by hand. While typing may be quicker, it’s also easier to just copy and paste what you’re reading without capturing the whole context of the idea. The slower process of handwriting notes requires you to be more deliberate with extracting ideas from the text. You also want to translate notes using your own language so they can be embedded into new contexts for your thinking.

“Write exactly one note for each idea and write as if you were writing for someone else: Use full sentences, disclose your sources, make references and try to be precise, clear and brief as possible.”

Step 1: Make Fleeting Notes. Fleeting notes are mere reminders of the ideas that pop into your head. Whether you are having a discussion with friends, attending a lecture, or suddenly have an idea while doing something else, you want to jot down a quick reminder then go back to whatever you’re doing.

Step 2: Make Literature Notes. Literature notes are notes about the content you're reading. You don't want to break your focus, so just make a brief record of the idea (“on page x it says y”) then direct your focus back to the text. The notes don’t need to be organized, just placed in your notebook that you keep beside you as you read. Follow these four guidelines for creating literature notes:

- Be extremely selective in what you write down

- Keep the note as short as possible

- Use your own words

- Write down the bibliographic details of the source

Side Note: I prefer to capture both my notes and highlights because I like having direct passages to quote in articles like this one. If I'm reading a physical book, I'll sticky tab the page where the quote came from so I can quickly find it later and input it in Readwise. If I'm reading on Kindle, my highlights and their location are automatically synced to Readwise.

Step 3: Make Permanent Notes. Permanent notes are the result of going through your notes from the first two steps and thinking about how they relate to what is relevant for your research, thinking, or interests. Ideally, you want to do this once a day before you forget the context of the notes you’ve already taken.

The goal is not to collect as many notes as possible, but to develop ideas, arguments, and discussions over time. This step is what separates the serious scholar from the casual note-taker.

Here are some questions you can ask yourself for deciding what should become a permanent note:

- Does the new information contradict, correct, support, or add to what you already know?

- Can you combine ideas to generate something new?

- What questions are triggered by these new ideas?

Write your permanent notes as if you were writing for someone else. That means using full sentences, disclosing your sources, making references, and trying to be as precise and brief as possible. Once you have created your permanent notes, throw away (or delete) your fleeting notes from step one and file your literature notes from step two into your slip-box.

Step 4: Add Permanent Notes to Your Slip-Box. Add your permanent notes to your slip-box by filing each note behind one or more related notes. If the note doesn’t directly relate to any other note yet, just file it at the very end. Also, be sure to add links to related notes.

Step 5: Develop Topics, Questions, and Research Projects Bottom-Up from Within the Slip-Box. Keep following your interests and taking more notes to develop your ideas further and observe where things will take you. The more you become interested in something, the more you will read and think about it, the more notes you will collect, and the more likely you will generate questions from it.

Instead of trying to brainstorm, your ideas and questions will come naturally from where your notes have developed and ideas have built up in clusters. See what is already there, what is missing, and what questions arise. Look for any gaps in your understanding that you can fill in with further reading.

"When it comes to finding good questions, it is therefore not enough to think about it. We have to do something with an idea before we know enough about it to make a good judgment. We have to work, write, connect, differentiate, complement and elaborate on questions - but this is what we do when we take smart notes."

Step 6: Decide On a Topic to Write About. Look through your slip-box to find what is most interesting. Your writing will be based around what you already have, not based on an unfounded idea about whatever book you're about to read might provide. Follow the connections between the relevant notes on your topic and bring them in order.

Step 7: Turn Your Notes into a Rough Draft. Don’t simply copy your notes into a rough draft, but translate them into something coherent and embed them into the context of your argument. As you detect any holes in your argument, fill them in, or change your argument.

Step 8: Edit and Proofread Your Manuscript. Refine your rough draft until it’s ready to be published.

In Summary:

When you turn the Smart Notes method into a daily habit, you no longer have to decide what to write about or worry about starting with a blank page. Just follow your interests, take simple notes while you read, convert the most important ideas into permanent notes, observe where your note-clusters have built up, then translate your notes into a template for your next work.

Read More on Amazon:

Subscribe to Lawson Blake

Get the latest posts delivered right to your inbox